The COVID-19 pandemic led inflation in Colombia to fall below the 3.0% target, reaching its lowest level in history of 1.51% in March 2021. However, in the second quarter of 2021, inflation began to rise to the point that in March 2023 it reached its highest peak (13.3%) since 1999. What explains this upturn in inflation? In a ecent research paper published in the series Working Papers on Economics, members of the technical staff of Banco de la República (the Central Bank of Colombia) address this question, and also analyze how the labor market adjusted during this process. This blog entry focuses on summarizing the main determinants found in the inflationary outbreak.

First, the inflationary outbreak was initially led by food prices, which started to increase since May 2021, as a result of a combination of domestic and external factors. Domestic factors involved road blockades that persistently affected the productive capacity of several products. Thus, one year later, food inflation in Colombia was higher than in most Latin American countries. Empirical studies found that road blockades explained about 9 percentage points (pp) of the difference. This factor was compounded by excessive rainfall in the last two years, which affected the production of various foods, especially perishables. As for external factors, the main supply shock was the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which affected the prices of agricultural inputs (e.g., fertilizers). This caused food inflation to increase worldwide, generating an external shock that combined with the idiosyncratic factors mentioned above and led to food inflation ending 2022 at 28%.

Second, beyond food, supply chain disruptions that affected global production and trade were initially behind the price increases in many groups of goods. This phenomenon was magnified by the sharp depreciation of the Colombian peso that occurred in 2021 and 2022, explained by external factors such as the tightening of international financial conditions and domestic factors such as local uncertainty and macro imbalances (fiscal and external). Thus, domestic prices continued to rise even after the fall in the costs of transportation and logistics and the reduction of world prices. Therefore, this sequence of external and domestic shocks of different nature produced a significant and persistent increase in headline inflation.

Third, it is noted that during the pandemic several relief measures were implemented, including temporary reductions in utility rates, freezing of fuel prices, and the temporary elimination of VAT and excise taxes on cell phone plans, hygiene products, restaurants, and hotels. The reversal of these measures was spread over time and has affected annual inflation in the most recent period, as the temporary price and rate reliefs were dismantled.

Fourth, domestic demand played an important role, the effect of which became noticeable a little later. The recovery of this demand after the pandemic was considerably faster and stronger than expected, led by private consumption and leveraged by strong credit growth. Public sector demand also played an important role, as evidenced by historically high fiscal deficits, when they were no longer explainable as a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis. Together, growth in consumer demand and public demand led to Colombian GDP reaching levels above pre-pandemic trends in 2022.

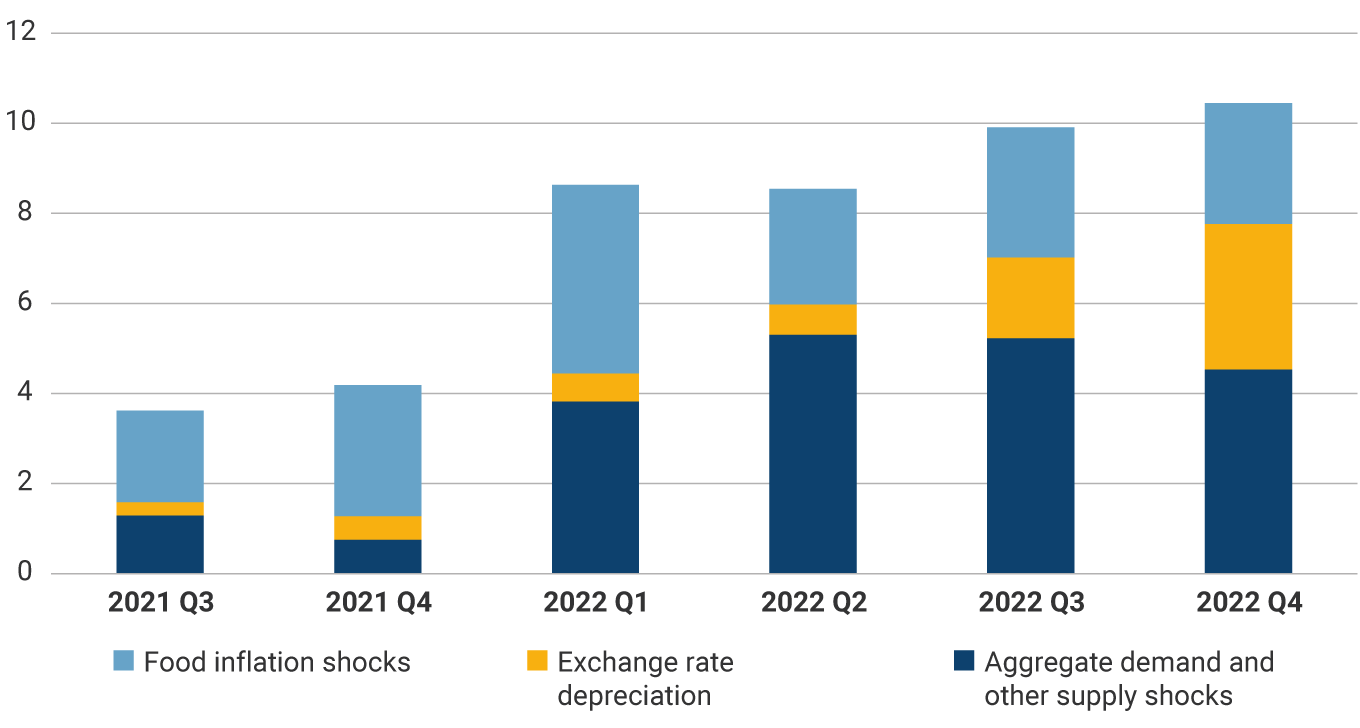

The previous description of the determinants of inflation is confirmed in Graph 1, which presents a decomposition of this variable with the help of the 4GM model, one of the central forecasting models used for the Monetary Policy Report. It is found that in the second half of 2021, food price shocks drove inflation, and that during 2022 these gradually lost relevance compared to the other shocks. However, by the end of 2022 they still accounted for about 25% of inflation. In contrast, shocks affecting the exchange rate contributed little in 2021 and in the first half of 2022 but gained relevance in the second half of 2022 to the point of accounting for about 30% of inflation by the end 2022. Finally, the other cost shocks and aggregate demand shocks, which were not a factor of obvious importance at the end of 2021, gained relevance during 2022. Thus, by the end of 2022, they explained about 45% of inflation.

Graph 1. Shock decomposition for annualized quarterly total inflation (deviations in percentage points from the 3.0% target)

Finally, several factors have added persistence to inflation, making its convergence process towards the 3.0% target likely to be longer and eventually more costly. First, inflation expectations increased to the point that all measures of expectations are above target at all time horizons. This increase in expectations partly explains the monetary policy response, as it shows that, although most of the determinants of the inflationary outbreak were initially supply factors (Graph 1), they permeated agents' expectations, thus making policy intervention necessary beyond the motive of correcting excess demand. Second, the persistence of inflation at high levels made indexation mechanisms begin to play a more prominent role. These indexation mechanisms affect some important prices, such as utilities and rents, and even the minimum wage, which, by regulation, must increase at least as per the inflation observed the previous year. It should be noted that in the latter case, the increases in 2022 and 2023 considerably exceeded the observed inflation, increasing the risk of a slower convergence of inflation to its target.