Education is the fundamental mechanism for accumulating human capital that allows social mobility across generations, overcoming poverty, and mitigating inequality. However, in Colombia, as in other developing countries, access to quality education has historically been unequal, mainly affecting vulnerable social and ethnic groups. To shed light on the historical roots of this inequality, a recent publication in the series Cuadernos de Historia Económica analyzes the current representation of specifically indigenous, Afro-Colombian, colonial elite, and modern elite surnames in educational institutions of varying quality. The study, in which Juliana Jaramillo Echeverri, a researcher at Banco de la República (the Central Bank of Colombia), participated, evaluates the current position of various historical groups in the country’s educational system.

In the study, the surnames of the colonial elite correspond to rare surnames of the encomenderos (from the Spanish verb encomendar, Spanish colonial officers) of the 17th century, students of the Colegio Mayor Nuestra Señora del Rosario and Colegio San Bartolomé in the 17th and 18th centuries, and slaveholders in the first half of the 19th century. In turn, the surnames of the modern elite correspond to those of the founders of the commercial banks in the 1870s and the founders of the Jockey Club in the early 20th century.

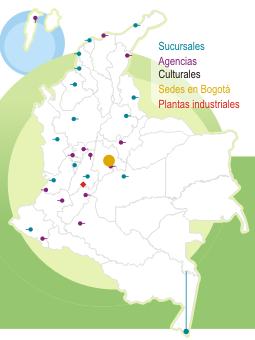

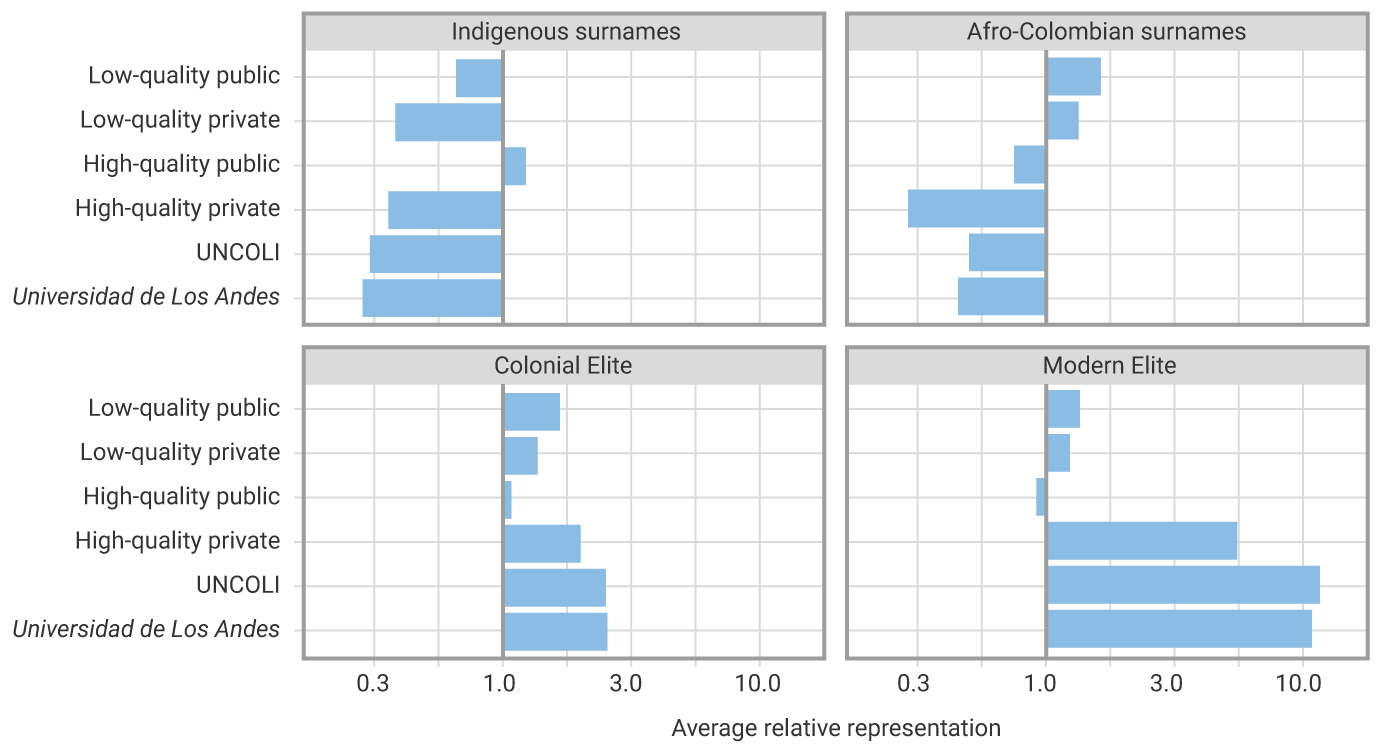

Using information from the Sistema Integrado de Matrículas (SIMAT in Spanish) and the Colombian Institute for the Promotion of Higher Education (ICFES in Spanish), a relative representation indicator was defined as the ratio between the participation of a surname in an institution over its share in the total population of students registered in SIMAT. When the indicator is higher than one (or less than one), the surnames under consideration are overrepresented (or underrepresented) in the institution concerned. Institutions are grouped according to their quality level and their public or private nature. High- and low-quality institutions are those in the top and bottom 5.0%, respectively, on the national standardized test. Additionally, schools belonging to the Unión de Colegios Internacionales de Bogotá (UNCOLI in Spanish) and Universidad de los Andes, which are good quality institutions that traditionally serve Colombia’s elites, are examined.

Graph 1 exhibits the average relative representation of the different historical groups in different types of educational institutions. As can be seen, the relative representation of elite surnames is greater than one in high-quality institutions, while the opposite is true for low-status surnames. For example, members of the modern elite appear in UNCOLI-affiliated schools at a rate 12 times higher than in the general population; in contrast, indigenous surnames appear at a rate that is 30% of their frequency in the population. In turn, the surnames of the colonial elite appear overrepresented nearly three times in high-quality institutions. Indigenous surnames are slightly overrepresented in high-quality public schools. In low-quality institutions, elite groups appear slightly overrepresented, while ethnic groups exhibit a distinctive pattern: Afro-Colombian surnames are overrepresented, and indigenous people are relatively absent.

The results of the study suggest that there is a persistence of inequality in access to quality education that has deep historical roots going back to the 19th century and beyond. Such persistence of status has been uneven among different groups, stressing the need to understand how the economic and social status of different groups changes or is maintained over time. The results are also consistent with the historical literature that has pointed out that colonial institutions, such as the encomienda and slavery, left long-term effects at both the national and subnational levels and contributed to the persistent lack of social mobility across generations associated with the differences in access to quality education that are still observed today. These results contrast with those observed in countries characterized by high coverage of high-quality public education, which typically plays a key role in achieving better outcomes concerning equity and intergenerational social mobility.

Image information

Un provinciano conduciendo a su hijo al Colegio

(A villager taking his son to school)

Artist: Ramón Torres Méndez

Year: ca. 1860

Technique: Illuminated lithography

Art Collection of Banco de la República

Photography: Oscar Monsalvee